Program notes:

October 25, 2009

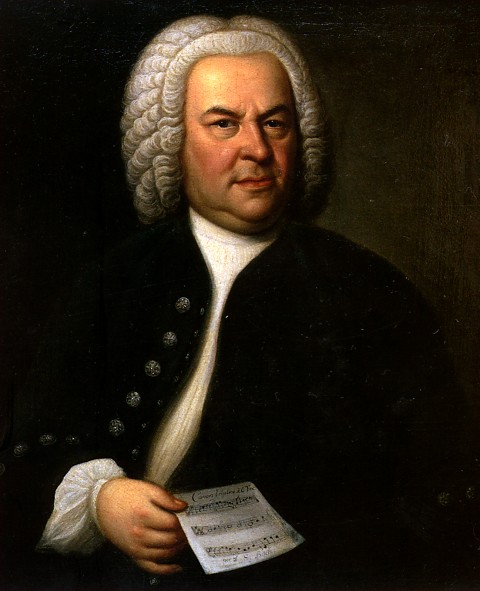

While the Baroque era lasted for only approximately 150 years, the music form this period (1600 – 1750) has influenced and developed later periods for almost 200 years. Johann Sebastian Bach’s works from his large musical output has been used in various settings, from liturgical services to technical studies to rich performances. Bach’s Partita No. 4 in D major, originally published separately in 1728, was compiled in 1731 as one of six partitas in a set titled, the Clavier Übung (Keyboard Exercise). Along with his English and French suites, the Partitas were Baroque-style collections of dances for solo keyboard. Like the Classical-style sonata that followed, the Baroque Partitas were composed with a strict formal scheme in mind. The first movement, the French overture (so-called “French” because the form was developed by the 17th century French composer Jean-Baptiste Lully), begins with a slow section, filled with dotted-rhythms, and is followed with the fugue, a style of composition in which a melodic figure is played and imitated in succession as different “voices.” The partita continues with the slow Allemande dance and the fast Courante. The series of dances is interrupted with a brief, yet charming melody in the Aria. Both the Sarabande and Minuet are slow triple meter dances, while the Gigue concludes the suite as a lively and rich triple meter dance that brings the fugue, one of the hallmarks of the Baroque era, to the forefront.

Although the popularity of Baroque music waned by the middle of the 18th century, the revival of Bach music by Felix Mendelssohn would greatly change music pedagogy in 19th century Europe. Frédéric Chopin’s early music education in his native Poland included a thorough study of counterpoint and fugue. His later compositions would be strongly influenced by Bach, for Chopin often carried with him the Well-Tempered Clavier wherever he traveled. Chopin was known for his beautiful motifs and expressive melodies, and this is especially true of his nocturnes. One can see Bach’s influence in how Chopin effortlessly employed counterpoint, harmony, and texture into his works, without which the melodies would not be as memorable.

The early 20th century was a time of various changes in the direction of classical music. Some composers experimented with atonal music, while others sought a return to older styles. The late romantic era was characterized by the slow erosion of tonality and regular tempo and the emerging Neobaroque movement revived the role of rhythm and counterpoint in music. Paul Hindemith’s Piano Sonata No. 3, composed in 1936, is written in four movements. The sonata-form first movement and scherzo second-movement are both rhythmically driven and developed using technical contrast. Following the third movement march, the last movement employs another tribute to Baroque music: the fugue. Paul Hindemith’s work reflects the approach of neoclassical composers; while the scope and structure of neoclassical compositions were clear and inspired from older forms, the intricate and specific components were more unique to 20th century music. Hindemith’s melodies and harmonies might be peculiar compares to those of Bach’s day, but they still maintain the sense of tonality and the appropriate resolution of dissonance into consonance.

The early 20th century was a time of various changes in the direction of classical music. Some composers experimented with atonal music, while others sought a return to older styles. The late romantic era was characterized by the slow erosion of tonality and regular tempo and the emerging Neobaroque movement revived the role of rhythm and counterpoint in music. Paul Hindemith’s Piano Sonata No. 3, composed in 1936, is written in four movements. The sonata-form first movement and scherzo second-movement are both rhythmically driven and developed using technical contrast. Following the third movement march, the last movement employs another tribute to Baroque music: the fugue. Paul Hindemith’s work reflects the approach of neoclassical composers; while the scope and structure of neoclassical compositions were clear and inspired from older forms, the intricate and specific components were more unique to 20th century music. Hindemith’s melodies and harmonies might be peculiar compares to those of Bach’s day, but they still maintain the sense of tonality and the appropriate resolution of dissonance into consonance.

Listen to a recording of me playing Hindemith’s Piano Sonata no. 3, Fugue here